The Mercury Line

The Tattooist Who Inked Bourdain, the Filmmaker Who had Multiple Kundalini Awakenings, and the Musician with a Missing Toe.

Kuching, Sarawak. February 2025.

The Kuching Waterfront Lodge is one of those hotels that survives by charm alone. Not expensive, but full of personality. Its narrow hallways smell faintly of mildew, the rooms are perpetually damp, and the décor walks a strange line between antique Chinese guesthouse and colonial oddity museum—bronze spears hung on blood-red walls, faded wall art imbued with symbolism, and animal skulls that loom over staircases like reminders. There’s a smoking atrium built into the heart of the building, enclosed but open to the light. That’s where I met C and K, two best friends travelling from Paris.

I was struggling to lock my room door. C offered help with the kind of casualness that makes you think he’s done it before—travelled solo, fumbled locks in strange places. He had a calming voice, and arms covered in tribal-style tattoos—thick black bands, woven motifs, markings that looked both ancient and intentionally placed. He had the kind of physical presence that’s hard to ignore, but he moved with ease, unassuming. When I mentioned I’d just come back from a stay in a longhouse, he smiled and said, “I stayed with the Iban too. Years ago, in my twenties. I was a shy kid then. Didn’t know who I was.” He told me how the women of the longhouse had taken him in, fed him, taught him to move with a kind of ease he didn’t yet possess. Eventually, the men brought him out to hunt. He learned how to walk quietly, how to read the jungle, how to survive off it. “They taught me everything,” he said. “I didn’t know it then, but that experience rewired something.”

Later, he told me something unexpected.

“I actually saw you for the first time 2 days ago,” he said. “That morning, probably when you were getting picked up by your tour guide outside of the hotel. You looked...a little lost.”

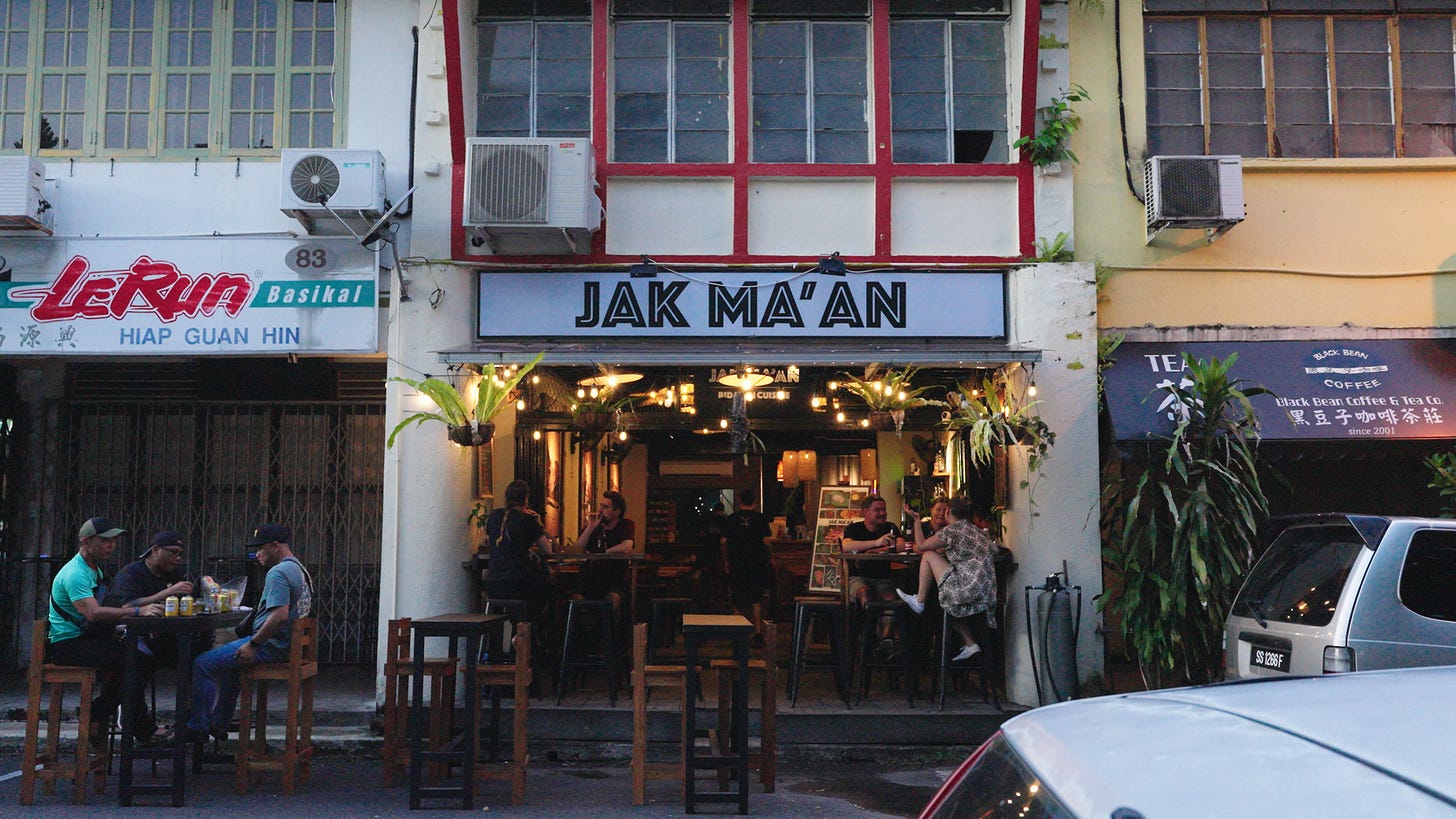

He smiled when he said it—not unkindly. Apparently, he’d seen me pacing in and out of the nearby convenience store, carrying an oversized backpack, debating which snacks or supplies to bring with me into the jungle. “You kept walking in, then coming out, then back in again,” he laughed. “It was like watching someone caught in a loop. I was intrigued.” We made plans to catch-up again in the evening at Jak Ma’An.

The night before I left for my own longhouse stay, I also met Desmond, a young Iban musician performing traditional songs at Jak Ma’An while drinking my mandatory carrot juice. He sat at the front entrance of the bar with his sape’—a long, carved lute whose tones hang heavy in the air, like smoke. His playing was precise, but never rigid. A small rattan basket sat beside him for donations.

Desmond used to be a rice farmer. He lost one of his toes to an infection after working barefoot in a flooded paddy field. He told me this softly, as if it was just part of the natural flow of things, a normal succession of events for a human being. After the amputation, he had to leave village life behind. Music became a new way of surviving. “It’s not much,” he said, “but it keeps me going.”

I asked him why he plays traditional songs. “So tourists know what it sounds like,” he replied. There was nothing nostalgic in his voice—just a kind of quiet responsibility.

That same morning after meeting C and K, I decided to try my luck finding Boi Skrang, a hand-tapping tattoo artist known around Sarawak for his flamboyant energy and uncompromising technique. I didn’t have an appointment. Just a name, an address, and a camera.

Boi was in. And he wasn’t quiet about it.

“Hello and welcome!” he shouted as I walked in. “You’re looking to get a traditional tattoo yeah?”

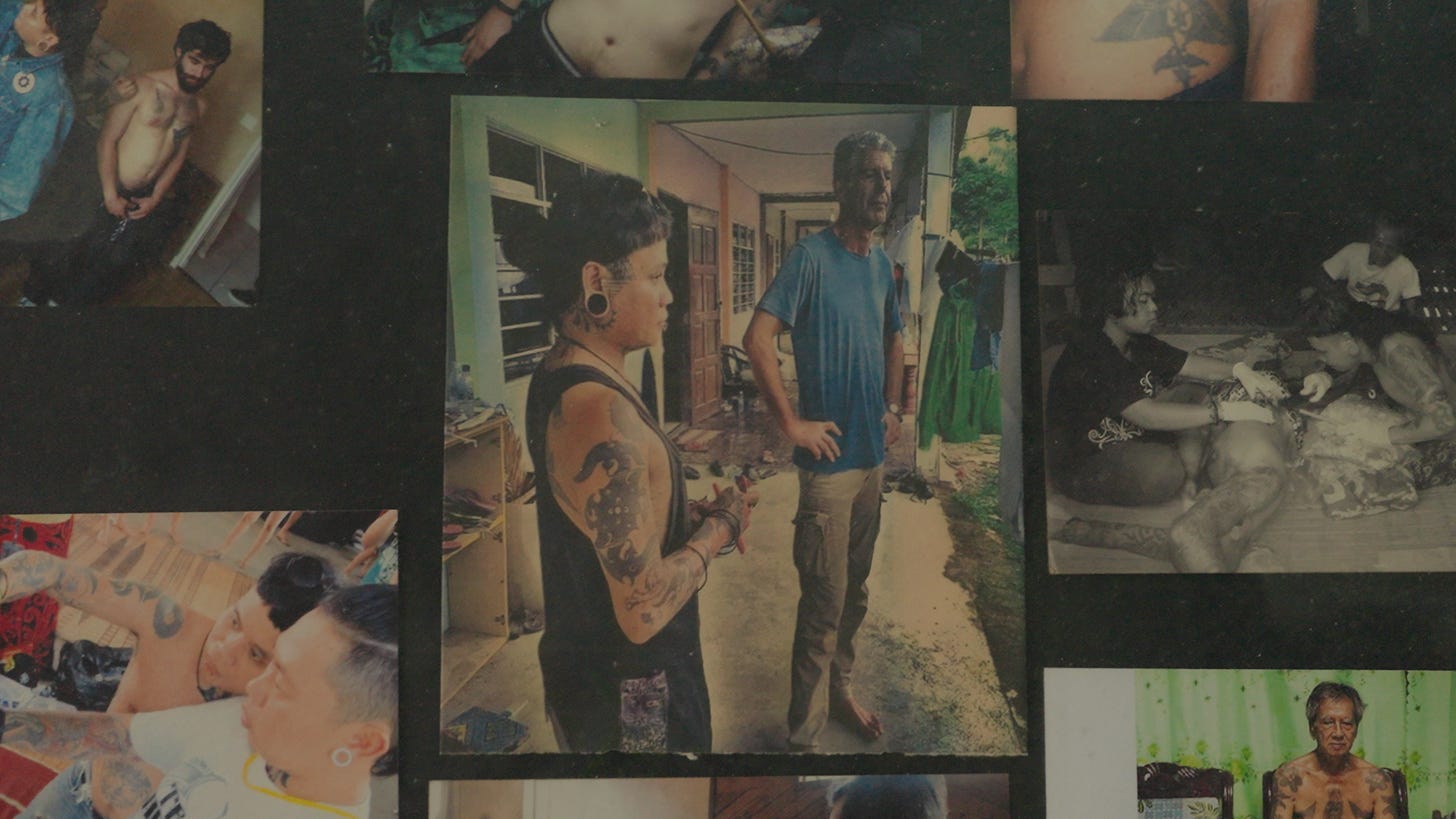

His studio was small but bursting with personality & rebellion—walls lined with Iban motifs, framed photos of past clients lying on their backs, blonde-haired and blue-eyed rockstar wannabes, surrounded by himself and other artists, framed newspaper clippings in French, and the occasional saucy calendar featuring naked women covered in tattoos. His tools were laid out like surgical instruments, but his vibe was anything but clinical.

Loud, warm, and quick to laugh, Boi moved with the confidence of someone whose work had already earned its place in the world.

“I tattooed Anthony Bourdain in my Longhouse. The second time he came back. Maybe 7 or 10 years ago?” He said.

I spent the evening at Jak Ma’An again. C and K were already seated.

The bar was glowing in that low-lit, late-night kind of way where everyone looks like they’ve already told their best story.

I first said hi to Greg and his friends, 3 English expats starting a cafe to fund the stray cats of Kuching whom I met 2 nights ago before sitting down at C and K’s table tucked away in an inconspicuous corner.

C spoke more about his past—about moments in his life when things bent in strange directions. He described what he called Kundalini awakenings, though not in spiritual jargon. More like weather events. He told me that during one of them, he walked the streets of Paris, sleepless for days, haunted by a voice that asked: Are you pure enough?

He said he could feel another one coming. “Next time,” he said, “I want it to happen somewhere in the jungle. Alone. Away from the noise.”

I told him, very much seriously, that I’d follow him with a camera. He nodded. No trace of irony. As if it had already been decided.

There was something about that night—the dim bar, the way the conversation unraveled into long stretches of silence, the sense that time had softened its grip—that reminded me of Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void, that early scene in Tokyo where reality feels like it’s about to peel back and show you something you’re not meant to see. Sitting there with C and K, it felt like the edge of something.

![Enter The Void – [FILMGRAB] Enter The Void – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!u0ap!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4c35a414-3b7b-43d3-a179-461cd51b2762_1280x544.jpeg)

Earlier that week, John, my guide who took me upriver to the Iban Longhouse, showed me photos of the Penan, the last nomadic people of Borneo still living completely off-grid. One photo showed a man returning from a hunt, blowpipe in hand, a deer slung over his shoulders. “No phone, no electricity. Nothing modern,” John said. “They live off the jungle. That’s it.”

The image stuck with me. Not because it was exotic. But because it felt unshaken—quietly outside of time.

Before the trip, I had looked up my astrocartography chart, just out of curiosity. It said Kuching falls on my Mercury line. Mercury rules communication, language, expression. At the time it felt like a novelty. But the week I spent here—encounters with musicians, tattooists, ex-hunters, strangers-like old friends in hotel atriums—seemed to unfold like a string of conversations I didn’t realise I was meant to have.

There’s something about Borneo that resists narrative. It doesn’t offer a tidy conclusion. It doesn’t hand over its wisdom in digestible portions. Instead, it gives you fragments: a song, a flashback to a movie you once loved, a cigarette in a damp hotel. A question in the middle of the night.

And sometimes, that’s all you really need. Not resolution. Just the reminder that people carry entire worlds inside them—and if you’re lucky, and listening, sometimes those worlds speak back.

-N from The PMJ

Watch our latest episode on YouTube

🎥 “Can Ancient Traditions Survive the Modern World? | Life Inside the Longhouse Part 2”

👉 Watch here